Can formal learning settings empower Māori tamariki?

Kia whakatōmuri te haere whakamua: ‘I walk backwards into the future with my eyes fixed on my past’.

What is Formal Learning?

Formal learning is intentional, structured and often determined by someone other than the learner (Eaton, 2010). A formal approach to learning and teaching typically includes a curriculum or a set of programmes that lead to a recognised qualification. Formal learning is often understood as a ‘one-size-fits-all’ approach (Eaton, 2010). Formal learning represents a narrow set of educational experiences that are often discontinuous from informal learning experiences in everyday life (Larike, Bronkhorst, Sanne, Akkerman, 2016).

Māori Immersion in Aotearoa New Zealand

Formal education predominantly draws on Western dominated approaches to teaching and learning, measuring abilities deemed valuable by Western society (Macfarlane & Macfarlane, 2012). Ākonga who are unable to learn in formal settings have been labelled unsuccessful learners (Tabacaru, 2018). For Māori, a discontinuity between cultural identity and Western dominated formal learning environments has perpetuated inequitable outcomes in education (MoE, 2008). In the 1970’s, less than 5% of Māori tamariki were fluent in te reo Māori, compared to over 90% of Māori ākonga in 1913 (Ministry for Culture & Heritage, 2022).

Due to the rapid decline of te reo and lose of cultural identity, the demand for Māori immersion has increased (NZEI Te Rui Roa, 2022). The first total Māori immersion preschool, Te Kōhanga Reo, was established in 1982 (Skerrett, 2018). Te Kōhanga Reo offers full exposure to te reo Māori within in a Māori cultural environment (Skerrett, 2018). Its rapid success paved the way for further Māori immersion schools, including Kura Kaupapa, designed for years 5 to 13 (Te Kōhanga Reo National Trust, n.d.).

Te Kōhanga Reo: Paving the Way for Māori Immersion

Nature and Philosophy

Te Kōhanga Reo translates to “the language nest” (Te Kōhanga Reo National Trust, n.d.). The philosophy of Kōhanga Reo is embedded in a Māori worldview (Hohepa, Smith, & McNaughton, 1992). Mokopuna are cared for alongside whānau in total immersion of te reo Māori, customs and values (Hohepa, Smith, & McNaughton, 1992). Whānau members typically include the parents of tamariki, community members and kaumātua (ERO, 2006). The intention is when whānau are working according to the philosophical aims of the Kōhanga Reo movement, tamariki’s education and wellbeing will benefit (Hohepa, Smith, & McNaughton, 1992). The philosophy of Kōhanga Reo aligns with sociocultural and situated theories of learning, due to the emphasis on collective learning through authentic cultural contexts (Rameka, 2011). Tamariki are understood within the context of the whānau, with the focus on mutual development and wellbeing situated within a Māori cultural environment (Kōhanga Reo National Trust Board, n.d.).

The following video illustrates how one Kōhanga Reo setting provides rich learning experiences for mokopuna, embedded in kaupapa Māori and whānau (PMEEA, 2019).

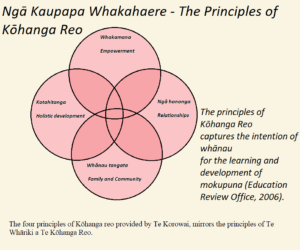

Te Korowai, articulates the principles, and policies for Kōhanga Reo based on a range of supporting documents, including Te Whāriki a Te Kōhanga Reo (Kōhanga reo National Trust Board, n.d.). It is the main guiding document for Kōhanga Reo to assist kaimahi and whānau in daily operation and whānau management (ERO, 2006). Te Whariki a Te Kōhanga Reo provides the purpose of learning, principles and strands (MoE, 2017). Te Whāriki a te Kōhanga Reo mirrors the principles and strands of Te Whāriki; Aotearoa’s bicultural ECE curriculum, while providing an Indigenous curriculum pathway of equal mana and status (MoE, 2017).

Te Korowai, articulates the principles, and policies for Kōhanga Reo based on a range of supporting documents, including Te Whāriki a Te Kōhanga Reo (Kōhanga reo National Trust Board, n.d.). It is the main guiding document for Kōhanga Reo to assist kaimahi and whānau in daily operation and whānau management (ERO, 2006). Te Whariki a Te Kōhanga Reo provides the purpose of learning, principles and strands (MoE, 2017). Te Whāriki a te Kōhanga Reo mirrors the principles and strands of Te Whāriki; Aotearoa’s bicultural ECE curriculum, while providing an Indigenous curriculum pathway of equal mana and status (MoE, 2017).

Kaupapa Māori Pedagogies

Kōhanga Reo applies teaching strategies that reflect Ngā Kaupapa Whakahaere (the four principles shown above) and Ngā taumata whakahirihiri, the five interconnected learning strands that are found in Te Whariki a te Kōhanga Reo (MoE, 2017). By implementing the strands and principles of Te Whariki, the treaty principle of participation is reflected (Macfarlane, 2012). Ngā Kaupapa Whakahaere underpins Ngā taumata whakahirihiri. Ako is reflected throughout the pedagogies, illustrating reciprocal teaching and learning between mokopuna, whānau and the environment (Rowe, 2020).

Ngā taumata whakahirihiri

Mana Whenua – Belonging

Pedagogies associated with mana whenua encourage tamariki to develop strong connections with their environment and ancestors (MoE, 2017). This may look like whānau supporting tamariki to learn their pepeha and participating at a local marae (ERO, 2006). Participation at a marae and hui supports the development of tamariki’s cultural and whānau identity (Cooper, Arago-Kemp, Wylie & Hogen, 2004). Developing a sense of belonging through a Kōhanga Reo setting builds whakamana, empowering mokopuna (MoE, 2017).

Mana Tangata – Contribution

Practices associated with Mana Tangata help to develop participation and respect for tamariki’s relationship to whānau, hapū and iwi (MoE, 2017). Through Kōhanga Reo, tamariki learn to actively participate in Māori cultural and whānau values (ERO, 2006). Language routines such as ‘ko wai au’ have been shown to help tamariki identify with their whānau ties (Farquahar, 2003). Whānau also model contribution to learning and relationships through ako. The practice of ako supports the principle of Ngā hononga – reflecting reciprocal, responsive relationships (MoE, 2017).

Kai’i (1990) found that despite the common approach of group learning in Kōhanga Reo, children were able to take responsibility for their own learning and for others. Through these group activities, tamariki are learning whānau responsibilities (Smith, 1987). Older children are often encouraged to help younger children and take on leadership roles (ERO, 2006). This reflects the important teacher-learner role of tuakana (older sibling)-teina (younger sibling) (Bourke, O’Neill & Loveridge, 2018).

Mana Reo – Communication

Tamariki are emersed in tikanga Māori and te reo. All instructions and guidance are given in te reo Māori. Opportunities for learning through pūrākau, waiata and kapahaka are provided (ERO, 200). According to Royal-Tangaere (1997), when tamariki use language within its cultural context, socialisation can occur. Kōhanga Reo provides a context for using te reo Māori as a vehicle for social interaction and development (MoE, 2006). In addition, cultural beliefs are sustained through strategies such as modelling and questioning, when combined with language routines (Farquahar, 2003).

Mana Aotūroa – Exploration

Tamariki develop knowledge of the natural and physical environment through Mana Aotūroa (MoE, 2006). Exploration of cultural knowledge is supported through using natural resources in learning activities, such as harvesting and weaving flax (ERO, 2006). Farquahar (2003) found tamariki’s ability to explore their environment is important for the promotion of positive educational outcomes. Tamahau Rowe illustrates that ako is intrinsically linked to the natural world. Ako recognises that we are all connected to the natural world as offspring of Ranginui (sky father) and Papatūanuku (earth mother) (Rowe, 2020).

Mana Atua – Wellbeing

Through teaching and learning about connections to people, place and spirituality, tamariki connect to their whakapapa and develop holistic wellbeing (Durie, 1997). Research shows that engagement with whānau, iwi and hapū is critical for the success and holistic wellbeing of Māori (Ritchie & Rau, 2006). Teaching and learning may include providing opportunities to engage with kaumatua, peers and whānau, and modelling respect and care for all things (ERO, 2006). Teaching and learning that enhances wellbeing through modelling positive behaviour and affirming cultural identity is supported by the principle of Kotahitanga (MoE, 2006).

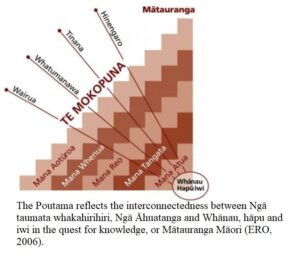

Ngā Āhuatanga

Ngā Āhuatanga is intertwined with the five strands of learning as evidence of effective outcomes for tamariki. Ngā Āhuatanga represents the four areas of holistic development: Tinana (the physical), Hinengaro (the mental), wairua (the spiritual), and whatumanawa (the emotional) (MoE, 2006).

Community Context

Kōhanga reo is rooted in facilitating a strong sense of community (MoE, 2006). Whānau and community engagement is the basis for the philosophy and pedagogy of Kōhanga reo (Kōhanga Reo National Trust Board, n.d.). Kōhanga Reo emphaises whole group participation in teaching and learning contexts, including the involvement of community members (Smith, 1987; Ka’ai, 1990). The concept of whānau and community is embedded in the observable behaviours within Kōhanga Reo and is defined by Smith (1987) as “inclusive behavior”. Mokopuna of all ages and ability interact with each other and with whānau, iwi and hapū (MoE 2006). Through community and whānau, tamariki affirm their identity and place in the world (Smith, 1987).

Critique and Implications

Concerns have been raised about the English ability of tamariki participating in Māori immersion schools. However, children in total immersion were found to be reading 2 years above their age in English, and benefiting emotionally (Keegan, 1996).

The success of Kōhanga Reo has implications for classroom pedagogy in mainstream settings (Ritchie, 2012). The education strategies found in Kōhanga Reo are actively sought by whānau. This suggests that particular socialisation activities and values may be reflected within the home (Stucki, n.d.). It is widely recognised that group learning is a preferred pedagogical approach for Māori (Stucki, n.d.). However, introducing collaborative teaching practices within mainstream settings, without the inclusion of other Māori pedagogical beliefs, values and practices, may not be as effective for the learning of Māori children (Stucki, n.d.). Māori ākonga achieve their potential when teaching and learning is culturally relevant (Bourke, Loveridge, & O’Neill, 2018).

Have you or your mokopuna experienced Kōhanga Reo? Comment below.

References

Bourke, R., Loveridge, J., & O’Neill, J. (2018). The impact of children’s everyday learning on teaching and learning in classrooms and across schools. Teaching & Learning Research Initiative.

Cooper, G, Arago-Kemp, V, Wylie, C & Hogen, E 2004. A Longitudinal Study of

Kōhanga Reo and Kura Kaupapa Māori Studies. Purongo Tuatahi, Phase One Report.

New Zealand Council for Educational Research. Te Runanga o Aotearoa mo

te Rangahau I te Matauranga, Wellington.

Durie, M. H. (1997). Māori Cultural Identity and Its Implications for Mental Health Services. International Journal of Mental Health, 26(3), 23–25. https://doi.org/10.1080/00207411.1997.11449407

D’Cunha, O. (2017). Living The Treaty of Waitangi through a bicultural pedagogy in early childhood. He Kupu, 5(2), 9–14.

Evaluation indicators for education reviews in kōhanga reo (Revised January 2006). (2006). Education Review Office, Te Tari Arotake Mātauranga.

Eaton, Sarah. (2010). Formal, non-formal and informal learning: What are the differences? Spring Institute of Intercultural Learning Newsletter.

Evaluation indicators for education reviews in kōhanga reo (Revised January 2006). (2006). Education Review Office, Te Tari Arotake Mātauranga.

Farquhar, S-E. (2003). Quality teaching early foundations: Best evidence

synthesis. Wellington: Ministry of Education.

Gunn, A. C., & Nuttall, J. G. (Eds.). (2019). Weaving Te Whariki: Aotearoa New Zealand’s early childhood curriculum document in theory and practice (3rd edition). NZCER Press.

Hohepa, M., Smith, L. T., & McNaughton, S. (1992). Te Kohanga Reo Hei Tikanga Ako i te Reo Maori: Te Kohanga Reo as a context for language learning. Educational Psychology, 12(3–4), 333–346.

Ka’ai, T. (1990) Te hiringa taketake: Mai te kohanga reo ki te kura. Thesis, University of Auckland

Keegan, P. J. (1996). The benefits of immersion education: a review of the New Zealand and overseas literature. New Zealand Council for Educational Research.

Larike, H. Bronkhorst, Sanne F. Akkerman, (2016) At the Boundary of School: Continuity and Discontinuity in learning across contexts, Educational Research Review. Volume 19.

Macfarlane, A. H., & Macfarlane, S. A. (2012). Diversity and inclusion in early childhood education: A bicultural approach to engaging Māori potential. In D. Gordon-Burns, A. C. Gunn, K. Purdue, N. Surtees (Eds.), Te aotūroa tātaki inclusive early childhood education: Perspectives on inclusion, social justice and equity from Aotearoa New Zealand (pp. 21-38). Wellington, New Zealand: NZCER Press.

Ministry for Culture & Heritage (2022, March 23). New Zealand History: First Kōhanga Reo Opens. First kōhanga reo opens (nzhistory.govt.nz)

Ministry of Education. (2008). Ka Hikitia: Managing for Success. Wellington, New Zealand: Ministry of Education

Ministry of Education. (2013). Tau mai te reo the Māori language in education strategy 2013 – 2017: Summary. Retrieved from http://www.education.govt.nz/assets/Documents/Ministry/Strategies-and[1]policies/TauMaiTeReoFullStrategy-English.pdf

Ministry of Education (2017) .Te Whāriki : he whāriki matauranga mō ngā mokopuna o Aotearoa : early childhood curriculum. Te Whāriki a te Kōhanga Reo ([Revised edition]).

Metge, J. (1983) Learning and teaching: He tikanga Maori. Research paper, Department of Education, Wellington

NZEI Te Rui Roa (2022). Ako: Jumping into Māori Immersion Learning. Jumping into Māori immersion learning – AKO (akojournal.org.nz)

Prime Minister’s Education Excellence Awards (2019, November 20). Te Kōhanga Reo o Tarimano, 2019 Finalist, Excellence in Engaging. YouTube. Te Kōhanga Reo ki Rotokawa, 2019 Winner, Excellence in Teaching & Learning – YouTube

Rameka, L. (2016). Kia whakatōmuri te haere whakamua: ‘I walk backwards into the future with my eyes fixed on my past’. Contemporary Issues in Early Childhood, 17(4), 387-398.

Rameka, L. K. (2011). Being Māori: Culturally relevant assessment in early childhood education. Early Years: An International Journal of Research and Development, 31(3), 245–256.

Ritchie, J., & Rau, C. (2006). Whakawhanaungatanga: Partnerships in bicultural development in early childhood care and education. Retrieved from http://www.tlri.org.nz/pdfs/9207_finalreport.pdf

Rowe. T. (2020). 256.701 Ako: Psychology of learning and teaching. Course material [Video]. https://webcast.massey.ac.nz/Mediasite/Play/d066c33343404e8ea0d60d38e487f5911d

Royal-Tangaere, A. (1997). Maori human development learning theory. In P. Te Whaiti, M.

McCarthy & A. Durie (Eds.), Mai i rangiatea: Maori wellbeing and development. Auckland,

New Zealand: Auckland University Press with Bridget Williams Books.

Ritchie, J., & Skerrett, M. (2013). Early childhood education in aotearoa new zealand : History, pedagogy, and liberation. Palgrave Macmillan.

Ritchie, J. (2012). An overview of early childhood care and education provision in ‘mainstream’ settings, in relation to kaupapa Māori curriculum and policy expectations. Pacific-Asian Education, 24(2), 9-22. Retrieved from http://unitec.researchbank.ac.nz/bitstream/handle/10652/2089/PAEJournal_v24n2_Ritchie.pdf?sequence=1

Smith, G. H. (1987) Akonga Maori: Preferred Maori teaching and learning methodologies. Discussion paper.

Stucki, P. (n.d.). Māori pedagogy, pedagogical beliefs and practices in a Māori tertiary institution : a thesis presented in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Education, Massey University.

Skerrett, M. (2018). Te kōhanga reo: early childhood education and the politics of language and cultural maintenance in Aotearoa, New Zealand – a personal–political story. In The SAGE Handbook of Early Childhood Policy (pp. 433-451). SAGE Publications Ltd, https://doi.org/10.4135/9781526402004

Te Kōhanga Reo National Trust Board (n.d.) Mō Te Kōhanga Reo: About Te Kōhanga Reo. Te Kōhanga Reo: Homepage (kohanga.ac.nz)