What is Informal Learning?

Informal learning is not confined to institutions or schools and has no formal curriculum (Jones & Brady, 2022). It is life-long learning that is embedded in everyday experiences (Bourke, O’Neill & Loveridge, 2018). Research has found that the majority of learning that occurs for tamariki is through learning from everyday experiences (Bourke, O’Neill & Loveridge, 2018). Unlike formal learning, informal learning is spontaneous and driven by the interests of the learner (Zürcher, 2010). Informal learning contexts often involves someone close to the learner, such as parent, sibling or grandparent (Dunst et al., 2006). Formal and informal learning is best understood as a continuum rather than as a dichotomy (Zürcher, 2010).

The Nature and Philosophy of Informal Learning Through Whānau

“Conditions for learning flourish in the interstices of family life” (Lave 1991, p. 78).

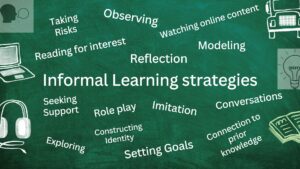

The nature of informal learning can be observed within the everyday interactions that occur between tamariki and whānau (Rona, Forster, & O’Neill, 2018). Informal learning through whānau involves the earliest experiences of children, from learning to walk, learning languages spoken within the home, to learning social skills (Jacobs, Harvey, & White, 2021). The inherently social nature of informal learning is reflected in the seven principles of informal learning below.

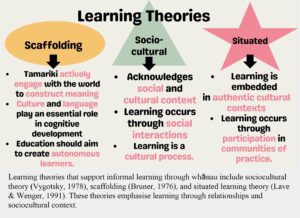

Learning that occurs through the context of is supported by several learning theories, as illustrated below.

Brunner’s Scaffolding Theory

Scaffolding can be defined as a process where an expert, or an informal teacher such as a parent or sibling or other whānau, provides support to a novice (Mermelshtine, 2017). The level of assistance is reduced as capability grows (Mermelshtine, 2017). Scaffolding is age appropriate, and respects autonomy while promoting problem solving (Bigelow, Macean & Proctor, 2004). Parental scaffolding can significantly influence development of executive functioning (EF), language development and cognitive ability in tamariki (Mermelshtine, 2017). For example, parents who provide warmth and responsiveness positively reinforce EF, while negative behaviours, such as intrusiveness or conflict, negatively impact the development of EF in tamariki (Mermelshtine, 2004). Scaffolding is a product of the family, as it is a bidirectional process that varies depending on the child, parents and context (Hughes & Ensor, 2009). Guided participation is a more fluid interpretation of scaffolding, emphasising that parent-child learning interactions are a function of their cultural context (Rogoff, 1990).

Vygotsky’s Sociocultural Theory

“Learning is a social activity that takes place within a social-cultural context” (Vygotsky, 1978).

Sociocultural theories inform our understanding of learning as a culturally and socially mediated process (Vygotsky, 1978). Sociocultural theory acknowledges that parents and whānau are the first teachers of tamariki, supporting understanding of the social, emotional, cognitive and physical world (Bornstein, 2015). Scaffolding theory shares similarities with sociocultural theory and Vygotsky’s Zone of Proximal Development (ZPD). ZPD illustrates the distance between actual development, where children can work independently, and potential development with support (Griffin & Cole, 1984). The process of scaffolding can be seen as the strategies used within the ZPD to promote development (Griffin & Cole, 1984). The sociocultural world of tamariki acts as a medium through which they can learn new skills with support, through guided participation within their ZPD (Della Porta, Sukmantari, et al., 2022). Both scaffolding and sociocultural theory recognises that informal teaching and learning is a reciprocal process situated in everyday informal contexts with those closest to tamariki.

Te Ao Māori

The importance of informal learning through whānau is supported by te ao Māori. Traditionally for Māori, the education of tamariki depended on whakapapa (genealogy) and whanaungatanga (relationships between whānau) (Royal-Tangaere, 1992). Within whakapapa exists the knowledge of histories, these guide tamariki to know their role in everyday life within their whānau (Royal, 2009). The reciprocal learning relationship of tuākana (older sibling) and teina (younger sibling) was seen as crucial for everyday learning (Royal, 2009). Reciprocal teaching and learning, known as ako, reflects how tamariki are socialised into community and family (Rona, Forster & O’Neill, 2018). Through ako, aspirations, responsibilities and values are realized (Rona, 2014). Each person learns and grows together. Ako embodies certain values, such as Manaaki, whānaungatanga and aroha (Rona, Forster & O’Neil, 2018). Reciprocity in teaching and learning cannot be separated from the values of whānau (Rona, Forster & O’Neill, 2018).

Relational Pedagogies

Tamariki use a range of strategies for learning from diverse pedagogical experiences with their whānau. Everyday informal learning is intrinsically connected to culture, belonging and self-understanding for tamariki (Bourke, Loveridge, & O’Neill, 2018).

Constructing Identity

Tamariki are exposed to family values from the moment of birth, which tamariki strategically observe when constructing their own identity (Rona, & Forster & O’Neill, 2018). Identity begins with whānau as even when tamariki are yet to develop an understanding of themselves, they are still able to recognise that they are members of a family group (Bourke, Loveridge, & O’Neill, 2018). Tamariki begin to understand their diverse ways of being by comparing their ‘self’ in their home environment with whānau, and their ‘self’ across contexts (Rona, Forster & O’Neil, 2018). A study on the informal learning experiences of Māori children by Rona, Forster and O’Neill (2018) found that tamariki may initially observe the behaviours of whānau, for example, in a marae setting. Tamariki may then begin to participate with intention, when helping to serve guests during powhiri. Tamariki recognise they are demonstrating whānau values such as manaakitanga (Rona, Forster & O’Neill, 2018). The process of ako begun from the moment of observing whānau. Social interactions with whānau across different social and cultural context is crucial for supporting tamariki to make sense of the world and find their place in it (Rona, Forster & O’Neill, 2018).

Taking Risks

Tamariki learn from the strategy of taking risks, which requires confidence and self-belief (Bourke, Lovridge & O’Neill, 2018). Taking risks often involves additional strategies, such as identifying the need to learn a new skill and approaching particular family members who can best provide support (Bourke, Lovridge & O’Neill, 2018). Taking risks in learning is supported by secure attachments. A secure attachment requires knowing that whānau can provide support when needed (Bowlby, 1969). Tamariki who are securely attached are more likely to find balance between seeking proximity to attachment figures and exploring their environment (Dujardin et al., 2016). Insecure attachment may lead to avoidance of proximity with attachment figures even when needing support, or avoidance of new experiences (Bosmans, et al., 2022). Tamariki who develop a secure attachment with parents are more resilient and willing to explore their environment. Secure attachment promotes the confidence for tamariki to take risks and develop more interest and attention in learning (Wang, 2021).

Connecting through Cultural Imitation

Tamariki use the strategy of high-fidelity imitation to connect to social and cultural groups (Legare & Nielsen, 2015). Unlink conceptual modelling, high-fidelity imitation involves faithful reproduction of methods, outcomes and intentions (Legare & Nielsen, 2015). Through imitation, tamariki acquire a wealth of cultural knowledge and affiliate with whānau and community (Legare & Nielsen, 2015). Imitation involves the interpretation of social cues and contextual informal in order to distinguish between instrumental and conventional behaviors (Legare & Nielsen, 2015). For example, cooking is both instrumental (preparing food to eat) and conventional behavior (preparing food to worship a deity) (Legare & Nielson, 2015). Through faithful imitation and interpretation of conventional cultural behaviors, tamariki connect with whānau and community. Tamariki move between the role of learner to teacher as they recognise their role in their whanau’s and community’s culture (Rona, Forster & O’Neill, 2018).

The following video of Taonga families weaving the tapa cloth illustrates the interconnectedness between learning, whānau, community and culture.

Community Context

The majority of learning that occurs for children is through learning from everyday experiences with whānau and their community (Rona, Forster & O’Neill, 2018). According to Bronfenbrenner (1979, 1997) children’s everyday life takes place within their community context. Within everyday life is the sociocultural order of a community that guides values, behaviors and rules that are required to participate and grow together (Rona, Forster & O’Neill, 2018). Both whānau and tamariki are influenced by the communities of practice they engage in. Everyone participates in a range of communities such as home, school, work and leisure (Wells, 2007). Wells (2007) states that the communities we participate in form our identity. Just as the communities we participate in contributes to informal learning, informal learning is necessary in order to learn about culture, and how to participate in various communities in everyday life (Gallimore, Goldberg, Weiser, 1993).

Implications for Whānau and Tamariki

The relevance of learning through whānau has important implications for parents and mainstream school settings. Researchers have noted the negative effects of the discontinuity between formal school education and informal learning for diverse students (Bourke, Loveridge & O’Neill, 2018). This dichotomy represents a ‘cultural discontinuity’ for learning and identity of tamariki (Taggart, 2017). Identity has a direct impact on motivation, with cultural disconnection in formal learning spaces negatively impacting motivation to learn (Taggart, 2017). Alternative formal learning contexts, such as Kōhanga Reo, aims to address cultural compatibility between the child’s home and school (Royal, 2012).

Reference

Bourke, R., Loveridge, J., & O’Neill, J. (2018). The impact of children’s everyday learning on teaching and learning in classrooms and across schools. Teaching & Learning Research Initiative.

Bosmans G, Van Vlierberghe L, Bakermans-Kranenburg MJ, Kobak R, Hermans D, van IJzendoorn MH. A Learning Theory Approach to Attachment Theory: Exploring Clinical Applications. Clin Child Fam Psychol Rev. 2022 Sep;25(3):591-612. doi: 10.1007/s10567-021-00377-x. Epub 2022 Jan 30. PMID: 35098428; PMCID: PMC8801239.

Della Porta SL, Sukmantari P, Howe N, Farhat F, Ross HS. Naturalistic Parent Teaching in the Home Environment During Early Childhood. Front Psychol. 2022 Mar 21;13:810400. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.810400. PMID: 35386906; PMCID: PMC8978720.

Gianola, M., & Losin, E. A. R. (2021). The neuroscience of cultural imitative learning and connections to global mental health. In J. Y. Chiao, S.-C. Li, R. Turner, S. Y. Lee-Tauler, & B. A. Pringle (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of cultural neuroscience and global mental health (pp. 326–363). Oxford University Press.

Jacobs, M. M., Harvey, N., & White, A. (2021). Parents and whānau as experts in their worlds: valuing family pedagogies in early childhood. Kōtuitui: New Zealand Journal of Social Sciences Online, 16(2), 265–282. https://doi.org/10.1080/1177083X.2021.1918187

Jones I, D. & Brady, G (2022) Informal Education Pedagogy Transcendence from the

‘Academy’ to Society in the Current and Post COVID Environment. Education

Sciences; 12(1):37. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci12010037

Koşkulu-Sancar, S., van de Weijer-Bergsma, E., Mulder, H., & Blom, E. (2023). Examining the role of parents and teachers in executive function development in early and middle childhood: A systematic review. Developmental Review, 67, 1–40. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dr.2022.101063

Legare, C.H., & Nielsen, M. (2015). Imitation and Innovation: The Dual Engines of Cultural Learning. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 19, 688-699.

McLean, K. C., & Syed, M. U. (Eds.). (2015). The Oxford handbook of identity development. Oxford University Press.

Mehri, Ehsan & Amerian, Majid. (2014). Scaffolding in Sociocultural Theory: Definition, Steps, Features, Conditions, Tools, and Effective Considerations. Scientific Journal of Review. 3. 756-765. 10.14196/sjr.v3i7.1505.

Parkinson, S., Brennan, F., Gleasure, S. & Linehan, E (2021) Evaluating the Relevance of Learner Identity for Educators and Adult Learners Post-COVID-19. Adult Learner: The Irish Journal of Adult and Community Education, p74-96 2021

Rona, Sarika & Forster, Margaret & O’Neill, John. (2018). Māori children’s everyday learning over the summer holidays. Learning, Culture and Social Interaction. 17. 10.1016/j.lcsi.2017.12.004.

Rona, S., Forster, M., & O’Neill, J. (2018). Māori children’s everyday learning over the summer holidays. Learning, Culture and Social Interaction, 17, 69–78. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lcsi.2017.12.004

Royal, T. (2009). Mātauranga Māori: an introduction. Retrieved from http://tur-dssubs1.massey.ac.nz.ezproxy.massey.ac.nz/handle/123456789/129.

Rogoff, Barbara & Callanan, Maureen & Gutierrez, Kris & Erickson, Frederick. (2016). The Organization of Informal Learning. Review of Research in Education. 40. 356-401. 10.3102/0091732X16680994.

Rogoff, B (2022) Learning by observing and pitching in. Retrieved from

https://stemforall2022.videohall.com/presentations/2274?display_media=video.

Retrieved 9 August 2023.

Wang, R. (2021) The Influence of Attachment Types on Academic Performance of Children. Proceedings of the 2021 4th International Conference on Humanities Education and Social Sciences. Atlantis Press.

Yuill, N., & Carr, A. (2018). Scaffolding: Integrating social and cognitive perspectives on children’s learning at home. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 88(2), 171–173. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjep.12227

Zürcher, R (2010). ‘Teaching-learning processes between informality and formalization’, The

encyclopaedia of pedagogy and informal education.

www.infed.org/informal_education/informality_and_formalization.htm. Accessed:

14 July 2023